Head over heels and AWOL

I wrote about Veto Baker before, but as its 50 years to the month that he ran out on the US military to be with the Vietnamese woman he loved, here's a redrafted essay about his wartime valour.

CAN YOU DESERT AN ARMY in the middle of a war and be a hero? In defence of the motion, let me tell you about Veto Huapili Baker1 from Hawaii.

Fifty years ago, Veto was a US marine. He was stationed in Danang, Central Vietnam, during the war (yes – that war). Now, Uncle Sam would no doubt have wanted Veto to be a killing machine but the young Hawaiian happened to be more of a lover than a fighter. We know this because in Danang he met, and fell for, a young woman called Mai, whom he wanted to marry. Unsurprisingly, Veto’s military superiors were not so open-minded about this cross-cultural romance and put the kibosh on any notion of nuptials. So, because all isn’t fair in love and war, one day in October 1972, Veto slipped out from the barracks to elope with Mai. The only hitch to the happy couple's union? Veto was now officially AWOL.

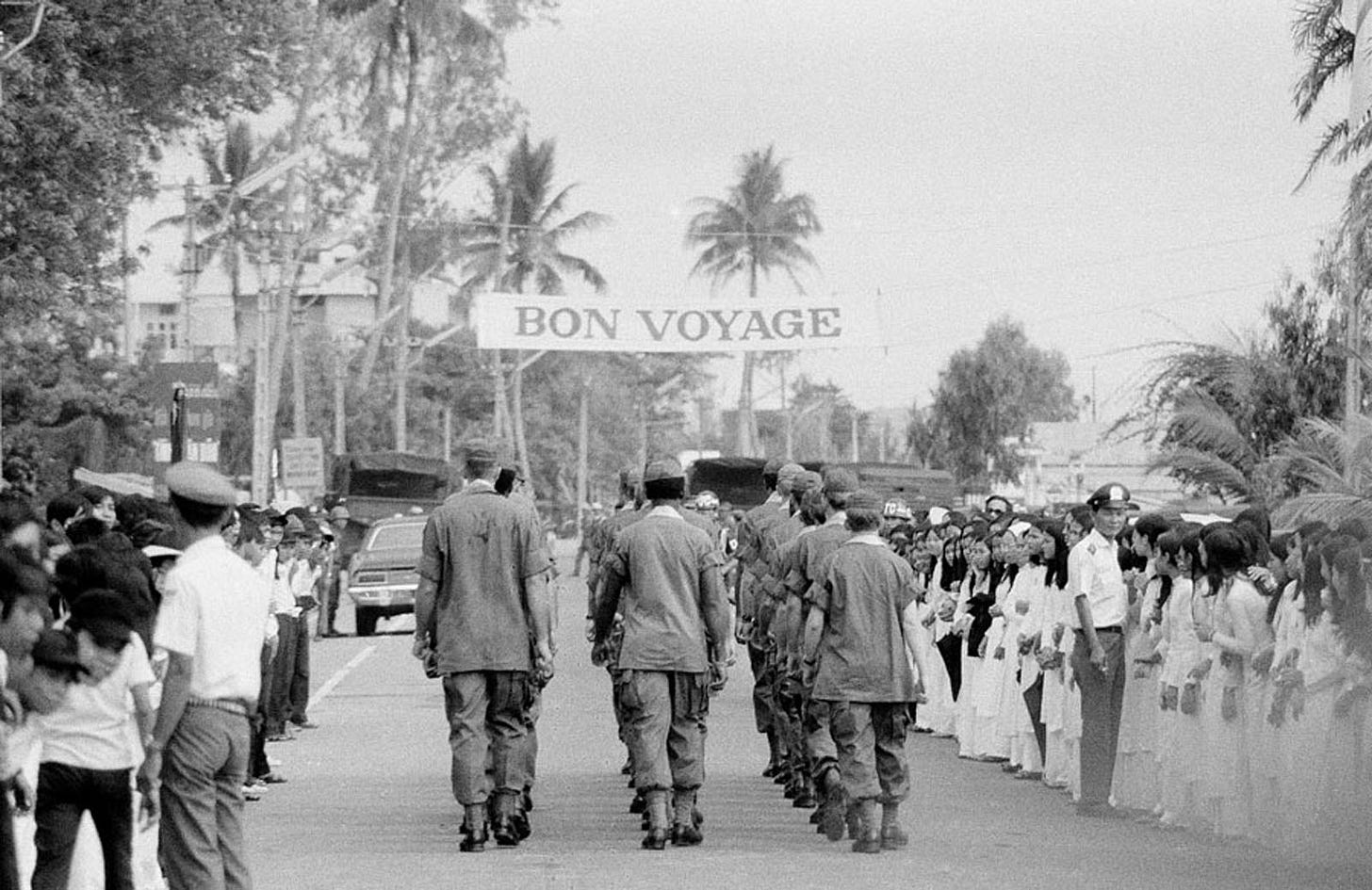

But if evading the Military Police was his biggest concern, maybe Veto didn’t have to keep a low profile for very long. By the end of March 1973, the US had pulled out of Vietnam. The war, for the Americans, was over. After that, well, with his Hawaiian complexion and slender build, apparently Veto integrated into the local tapestry well enough. One source – the journalist Al Dawson, who was the Saigon-based bureau chief of UPI until 1975 – told me Veto did odd jobs on the streets, like fixing motorcycles. I also read that he worked with a road construction crew up in the mountains and may have even earned a crust from hunting and teaching English.

However he spent his days, seasons came, seasons went. Veto and Mai had one kid and then another. But they must have known that these salad days in Danang couldn't last. The northern Vietnamese forces (officially the 'People's Army of Vietnam') would soon win the war, officially unifying north and south Vietnam as one country on April 30, 1975. Needless to say, no American ‘stay behind’ anywhere in the former south would ever be trusted by the in-coming communist intelligence network. So, in 1976, Veto, a heavily pregnant Mai and their two kids, Bah and Ho, were escorted to Saigon and turned over to the Red Cross, which helped the deportees travel to the US via Thailand.

I know very little about what happened to Veto on American soil, but I have been told that American government agents did ‘check in’ with him, even in the 1980s. They were undoubtedly keen to know what this deserter had been doing in Danang and, most importantly, who he might have seen, either in the city or its environs (ever since the US military called it quits in Vietnam, stories and sightings of POWs as well as mysterious deserters who allegedly joined the other side have persisted till the present day, but sure, I know you’ve all seen Rambo: First Blood Part II).

But personally, I like to imagine that Veto's day-to-day life in Danang was pleasantly mundane and routinely domestic (family meals, fractious babies, awkward conversations with the in laws, etc). If I were to interview him, I'd probably ask him what he usually ate for breakfast, lunch and dinner, or if he learned to stomach the pungent fermented dips that grace every table in Central Vietnam at mealtimes. I'd probably also ask what kind of two-stroke he rode around town, and if he ever went to the top of the Hai Van pass – a mountainous, coast-hugging road that offers sweeping views of what the Vietnamese call the East Sea – and gazed in the direction of the Pacific and his ancestral home...

Thinking that I could possibly learn the answers to some of the above, I had begun to wonder if Veto were still alive. So one evening, sitting in my apartment in Ho Chi Minh City, like all feckless 21st century reporters, I turned to Facebook and typed in his name. First, I found mention of Veto’s brother, now a master hula teacher and performer in Hawaii. Via a third party the brother wrote to me, saying that Veto now lives in Chandler, Arizona to be closer to some of his kids, and grandkids, and great-grandkids. He added that Veto and Mai’s story made him love, of all things, the Broadway show 'Miss Saigon' but, unlike the musical, where the marine leaves the girl, the brother noted: "Veto loved Mai so much that he went AWOL."

I pressed the intermediary for a direct contact (as tactfully as I could), but they had disappeared into the ether and the digital trail to Veto went cold again. Then — just as I’d given up on the story – in late 2021, I discovered a new Facebook profile with the name Veto Huapili Baker. The avatar was a picture of elderly couple and yes, it could only be Veto and Mai, still alive, and looking like they were very much in love, judging by their wide grins. I chanced my arm and wrote a few messages – explaining who I was, how I'd heard of Veto, and how I was moved by his and Mai's story.

The messages went unread for weeks and my own life started to move on once again. But then one evening, at the tail end of the rainy season in Saigon, I opened Facebook to find a reply, not written by Veto, but his granddaughter Kēhau, who periodically checks her grandfather’s Facebook page. She told me that Veto and Mai are not very emotional people, but “their eyes swelled up and noses became runny” when she told them why I had wanted to contact them. “I could tell your messages really touched their pu’uwai (heart),” she wrote.

Still thinking that as a writer I should push for more, I thought about trying to explain in more detail why I found Veto's deeds so wonderful – because, in the midst of an ugly war and through his actions, if not his words, he had shown true valour by turning to Mai and asking her the only question that counts for two lovers on the run: ‘Take my hand quick and tell me, what have you in your heart2.’

But then I thought about how these runaway lovers, some 50 years after Veto fell head over heels for Mai and went AWOL, were now the happy totems of a cross-cultural tribe with 21 grandkids and a growing number of great-grandkids – and I realised I know everything I need to know about Veto Huapili Baker – he’s a war hero, one that deserves to be left in peace.

I previously wrote, a little whimsically, about how one day I hoped someone would open a bar in Danang called Veto’s, and in that way, perhaps his story would be quietly shared and remembered. But earlier this year, I pulled that piece off Substack/ Medium and rewrote this story (the one you have just read) as I wanted to submit it to the Irish broadcaster RTE’s show Sunday Miscellany. But I only a four-week window in Dublin (and they never replied anyway) so that didn’t come to pass. It was only today that I realised it’s exactly 50 years to the month since Veto skipped out on his superiors, so the timing seemed right to slap this up here.

Interesting and touching.

Do many people go awol in Vietnam? How hard is it to trace?

Kind regards

Susan