The life and times of ‘Madame Canon’

Madeleine O’Connell was a French plantation owner, who died in a skirmish in Tây Ninh in 1947. Her story is a good one, but complex too, so here’s what I know.

If Madame Canon is killed, it is more than a general who will disappear.”

I

SAIGON, EARLY JANUARY, 1947.

The monsoonal rains ended some weeks ago, and lately the air has been drier, the streets a little cooler. When a breeze blows a smattering of leaves from the tamarind trees along Rue Lagrandière, you could, if only for a fleeting moment, think that this city even has an autumn. But the trees shed leaves all year-round here. From the strain of survival in the tropics, you suppose.

This morning, when you left your apartment on Rue Chasseloup-Laubat, and walked to your office on Rue Catinat, you thought, if only it could always be like this! But now midday is approaching, and if you walked under the blazing sun, you’d wither as quickly as the fallen leaves. My god, the thought of enduring another long dry season fills you with fatigue – you can already feel the first beads of sweat rolling down the inside of your shirt, and you feel a little guilty being so impatient for a funeral procession to get going, but wait… at last, yes, there… down the road, you can see the procession making its way from the Military Hospital. As it approaches you can see the little red coffin has been draped in the French flag and placed on a horse drawn carriage. Walking alongside family members of the deceased, who else but the commissioner himself – the stiff-backed and stately Pierre Boyer de La Tour du Moulin, going through the motions in more ways than one. And just to his left, ah yes, the ‘President of the Autonomous Republic of Cochinchina’, Nguyen Van Xuan, looking as loyal and out of place as ever. More uniformed officers, diplomats and other notables follow with their heads down, everyone playing their part with solemn aplomb – it is a State funeral, after all. But along the roadside, and following the procession, dozens of Annamites have come to pay their respects, too. Madame Canon. Ba Lon. Madeleine. Ma’man. Well, no matter what they call her, none of them would believe it if you told them that the poor woman died for nothing. Yesterday at Café de la Terrasse, as you sat pretending to read your ‘Courrier de Saïgon’, you overheard whispers that General Latour will award Madame O’Connell the Croix de Guerre with a silver star to boot. But if she is a symbol of France’s destiny, well, there you have it – a coffin wrapped in a flag that is about to be buried six feet under. Someone should telegram De Gaulle and tell that stubborn fool this is the dress rehearsal for the bitter end of Indochina. It has already begun – you can’t be alone in thinking that? Everything is unravelling, inside and outside the city, and soon, because you’re a coward, you – an office-bound clerk of no consequence – will do what Madeleine O’Connell never would have done. You will pack your bags. You will save your own skin. You will leave Saigon forever.

The horse-drawn carriage trundles onward to the cemetery on rue de Bangkok. The procession soon follows it around the corner. And you? Now that everyone has passed you by, you are free to whimper then weep.

II

HO CHI MINH CITY, 2025

I first came across the name Marie-Madeleine O’Connell a.k.a Madame Canon some years ago when dipping in and out of the Penguin History of Modern Vietnam – a formidable scholarly work by Christopher Goscha. In a chapter detailing the tumultuous political climate in Cochinchine (southern Vietnam) in the late 1940s, I noted a captivating line: “Madeleine O’Connell, the daughter of Irish immigrants who had come to Indochina to make their fortune, armed her plantation [...] and herself so heavily that Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) agents referred to her as ‘Madame Canon’...”

It was a tantalising historical snippet, especially for an Irishman living long-term in Vietnam, so I did a little online digging and found an obituary (published by a magazine called Tropiques in 1949) that read like colonial propaganda with lines such as: “They [the Viet Minh1] have assassinated an indomitable Frenchwoman – a true Joan of Arc of ethical colonisation – always on horseback or in a car, managing her plantations better than ten men could have…”

These days, the story of Madeleine O’Connell, who was indeed killed in a firefight with Viet Minh forces on December 30, 1947, is definitely not well known. Even the brief description of her as ‘the daughter of Irish immigrants’ isn’t accurate – Madeleine O’Connell’s maiden name was Labbé and she was born to French parents in the northeastern province of Quang Yen (part of Tonkin at the time). At the age of 15, she married a Frenchman called Daniel O’Connell (17), a name that will have many Irish people doing a double take.

Indeed, on the social media platform formerly known as Twitter, some time ago, a researcher claimed (or rather, they assumed) that Madeleine O’Connell was a fabulously heroic descendent of Daniel O’Connell (1775 - 1841), one of 19th-century Ireland’s most influential political figures.

For those that don’t know the name, Daniel O’Connell was not an armed revolutionary – far from it. He was a successful lawyer and brilliant orator who mobilised the colonised and landless Irish peasantry through sheer force of speech and political conviction. He was also a skilled parliamentarian, who lobbied the British establishment in the House of Commons tirelessly, trying to secure Catholic emancipation and advocate for greater Irish self-governance.

When trying to figure out what ‘parish’ (in the old country) the O’Connells of Indochina may have sprung from, I turned to my aunt, Phil Stokes, a keen genealogist. She ascertained that Jean Louis O'Connell (Madeleine’s father-in-law) was born in British India in 1866 and his father Timothy was born in Ireland but in county Offaly (not county Kerry, where the political leader Daniel O'Connell was born). At some stage in the 19th century, Timothy emigrated and then served in the British Army in India. After retiring with a pension, he was employed as a policeman, rising to police chief in Tamil Nadu (southern India). And how did this Irish fellow become French? At some stage he may have done a stint in a French colony in East Africa, where he met and wed a French woman. Or perhaps that occurred in India. Either way, Timothy became ‘Timothée’ and it seems he never returned to the green, green grass of county Offaly – and why would he have done, when the Great Famine (1845 to 1852) had decimated Ireland and led to the death or emigration of 25% of the Irish population. Suffice to say, if there is a genetic link between Daniel O’Connell of Ireland and Daniel O’Connell of Indochina it is very distant – and there's none to Madeleine.

The aforementioned social media post also claimed that Madeleine and her family were ‘working for the resistance in World War 2 in far flung Vietnam’ – a rather misleading statement that was, predictably, retweeted by dozens, who were easily seduced by the thought of a French woman with Irish blood and a revolutionary spirit ‘working for the resistance’. Now, while it is true she hid and transported weapons for the French army (when the French colonial rulers were effectively overthrown in a coup by the Japanese military in March, 1945), she was still a colonial landowner trying to defend her plantation and assist a colonial state reassert its military dominance (and continue its systematic exploitation of ‘far flung Vietnam’).

Not that she wasn’t brave or heroic. I mean, by the sounds of it, she was a total badass. But hang on, I’ll get to that later…

III

NOW I CAN ONLY SPEAK FOR MYSELF, but if I were trying to paint a picture of a French colonial family on a rubber plantation, some 80 or 90 years ago, I would once have conjured up a horrid patriarch with a pith helmet – a florid-faced, jowly fellow, overdressed for tropical heat and sweating profusely, perhaps after whipping some coolies with a stick. His children? Isolated from ‘Les Annamites’ and learning table manners from a stern governess, they are caught between worlds. As for their pallid mother, stricken with homesickness and drained by the enervating heat, she’s convalescing in Dalat, where ailing French émigrés are treated with shots of quinine and snifters of port until they keel over and die.

But the Labbé and O’Connell families fly in the face of these ghastly stereotypes. Madeleine’s father, Monsieur Labbé started out as an administrator of the Civil Services in Indochina and rose through the ranks to become the Director of the Superior Residence Bureau in Hué, where he insisted his children learn to speak le dialecte annamite, and where he was well known to, and well regarded by, the Nguyen royal family.

And then we have Daniel’s father, Joseph O'Connell, who served as the Administrator of the Civil Services. Alas, he was far too localised and atypical (so, too nice?) in the eyes of his colonial superiors, so in 1914, he was dispatched to the penal colony of Poulo-Condore (Con Dao Island today), an appointment that was well understood to be a form of punishment. Far removed from colonial society, O’Connell got the attention of his prisoners – not for his cruelty but his kindness. That might sound unlikely for a prison better known for torture and tiger cages, but the revolutionary leader Huynh Thuc Khang (a future acting president of Vietnam) spent 13 years in a cell on Poulo-Condore and, in his memoirs, Thi tù tùng thoai, he singled out Joseph O'Connell, praising him for his humanity and restoring the prisoners’ dignity.

After her wedding – an arranged marriage, perhaps? – Madeleine relocated to Cochinchina (southern Vietnam today) with her husband, Daniel, to take over management of the O’Connell family’s rubber plantation in Tây Ninh2.

At the time, rubber was big business and a cornerstone of France’s colonial economy. Indochina produced tens of thousands of tonnes annually, with rubber exports accounting for up to half of the colony’s revenues in certain years. For the O’Connells, the plantation was a shrewd and lucrative investment. By 1915, the O’Connell plantation in Tây Ninh spanned 12 hectares and yielded around 5 tonnes of dry rubber, valued at approximately 24,000 piastres — a substantial sum in the colonial economy.

In addition to rubber, the plantation also grew cassava, peanuts, and tobacco, and maintained livestock – even sheep, an animal not native to the region. The estate featured its own brickworks and processing facilities, operated by a sizeable labour force. Madeleine and Daniel – when he was there – lived in a large villa with Art Deco interiors, where they raised their three sons: Patrick, Guy, and Roger.

Upon entering the Eaux et Forêts (Water and Forests Service) in 1921, Daniel pursued his career, rising steadily through the ranks, and travelling frequently. An archival note that I found indicates he was much admired for his modesty, fluent Vietnamese, and deep environmental knowledge of Indochina’s forests. Besides being decorated with honours, including the Royal Order of Cambodia, he was also a handsome chap judging by a picture of him at Angkor Wat (see below). But one could argue that Daniel embodied the contradictions of the colonial project itself – a man who, on paper, studied forest conservation, but in practice also owned plantations that stripped the land bare, commodified it, and scrubbed it of biodiversity.

With Daniel often on the road, Madeleine managed the plantation, rising before dawn, overseeing operations, often forgetting to eat, and toiling alongside the peasants, according to the obituary in Tropiques. No perfume, no parasol, no fashions imported from France for this young lady! She was a true pioneer – one who, we are told, gamely hacked through the forest with a machete to hunt wild oxen, gaur, deer, tigers, and elephants, sometimes to feed those working on her land, sometimes to protect them. She cared for the elderly, and is said to have taken in twenty abandoned children, raising them on the plantation. Even before the second World War arrived, the locals called her Bà Lớn – the “Great Lady.”3

Again, we have to remember the writer of the obituary had a purpose – he was using Madeleine as a model of ethical colonisation to justify the continued presence of the French in Indochina. We never hear Vietnamese voices in his account and their affection is assumed with one notable exception – we are told that families in the region considered her (after her death) to be a protective spirit – a “Tutelary Genius” (Thần hộ mệnh) – of their land.

However, as a quick but illuminating aside, in Vietnam, a person who dies under heroic circumstances or as a martyr can be venerated as a local spirit. These spirits, often honoured at communal houses or village temples (small or large), are routinely worshipped and thanked with offerings so they will continue to protect the land and its people. So this “spiritual assimilation” of Madame Canon is striking – essentially a colonial figure (and Catholic, I assume) became part of the local cosmology, which is quite something. We know this is likely to be true as in 1997, a pagoda at Thanh-Diên (outside of Tay Ninh town) returned Madeleine’s ancestral tablets (bài vị) to her grandson Gérard O’Connell – these tablets were apparently ‘hidden’, perhaps for political reasons in communist Vietnam.

What I have always liked about the story of Madeleine O’Connell is that it’s complicated. Too often – especially in this age of social media – history gets boiled down to overly simplified narratives: heroes and villains, victims and oppressors, saints and sinners. But all of this can be true: Marie-Madeleine O’Connell was a woman of courage and conviction, who treated Vietnamese peasants decently (for the standards of the time) but who also operated an enterprise that was part of a brutal colonial structure; she also weaponised her plantation to protect it from anti-colonial forces as well as hid and smuggled arms for the beleaguered French troops. She even survived a brutal attack in her own home (the attackers were described as ‘Japanese collaborators’ in the text I found), and of course, ultimately, she died in a firefight, all guns blazing…

To understand all of that, let’s take a closer look at the tumultuous atmosphere of Cochinchine during the 1940s – a time when the colonial order was in disarray, the Japanese occupation had fractured whatever uneasy equilibrium the French had maintained, and Vietnamese nationalists of every stripe had begun to seize their moment. In short, it was a chaotic time.

IV

BY JUNE 1940, THE FRENCH OF FRANCE had capitulated to Germany, and the colonial forces of the Third Republic were also unable to resist the Japanese moving into Indochina. Although the French retained sovereignty over Tonkin, by autumn of the same year, they had allowed 6,000 Japanese troops into the country, opening the way for what Christopher Goscha describes as “a troubled but unique imperial condominium in Indochina”.

At the heart of this uneasy dual arrangement of power was the Japanese preference to let the French run the administration (they were more focused on military matters at first). But with French Indochina evidently on the wane – large swathes of Cambodia and Laos were annexed by Thailand (Siam) in 1941 – the Japanese planned to take full advantage, expanding their military presence in southern Indochina to 75,000. They also took over monetary policy and began to extract rice and other resources for themselves. Observing this from afar, the US President Roosevelt decided to freeze Japanese assets in America and impose an embargo on Tokyo. From there, things escalated – the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbour and other US naval bases across the Asia Pacific region (including Guam, the Philippines, and British Malaya) in late 1941. With the Americans initially focused on Europe, the Japanese basically had the run of Southeast Asia, overthrowing the British in Malaya (December 1941), Singapore (February 1942) and Burma (January to May 1942).

In Cochinchine (southern Vietnam), the French had no choice but to kowtow to the Japanese who took what they wanted4.

Simmering beneath the surface was a Vietnamese intelligentsia that felt betrayed by the Japanese, who had supposedly come to liberate the Vietnamese. When a number of diehard lieutenants from Phan Bội Châu’s Go East (Đông Du) Program – a nationalist movement that encouraged young Vietnamese to study in Japan and acquire the modern knowledge they needed to liberate Vietnam from French colonial rule – tried to seize power, the Japanese let French forces crush them. The Japanese had initially claimed they would develop a ‘Co-Prosperity Sphere’ for a bloc of Asian countries but their hapless governance and plundering of resources soon crippled the country. In 1945, approximately one million peasants died from famine. Tapping the growing resentment of the masses, the nationalist movement led by none other than Ho Chi Minh was gathering pace. He would declare independence in Hanoi on September 2, 1945, which marked the formal birth of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV), headquartered in the north, while the French clung to their remaining authority in Cochinchina in the south. In the same month British troops (inclusive of the famous Gurkhas) entered Saigon, ostensibly to maintain order. Or rather restore it for the French (‘Hello chaps, I hear you’re in a bit of a pickle?’). In one of her acts of valour for the French cause, Madeleine O’Connell apparently met and hid British paratroopers, who landed in Tay Ninh.

Essentially reinvading their own colony5, the French, however, were unable to reassert absolute authority. The Viet Minh were pushing hard into the south (Nam Bộ, as they called it). under the command of Nguyen Binh, an ex-convict, who had lost his eye in a prison melee. A charismatic, streetwise and smart tactician, he had taken to wearing a Japanese military gabardine and a long Mikado sabre when tasked with fighting ‘an angry war’ against the French. Also in the mix – and please forgive me if I skip the detailed introductions – were the Binh Xuyen (an organized crime syndicate turned militia), Cao Dai (a syncretic religious sect with its own army), and Hoa Hao (a Buddhist reformist movement with strong peasant support) – three movements that had their own aspirations for an autonomous proto-state in southern Vietnam. All of which is to say, there was an awful lot going on…6

As administrative states, the DRV and the French territories were pretty much archipelagoes that expanded and contracted as armies moved in and out of them. Manpower was a chronic issue for both sides. In 1947, for example, French forces designated for Indochina were diverted to suppress an uprising in Madagascar, revealing the limits of France’s overstretched imperial apparatus. Meanwhile, the DRV leadership hesitated to impose a national conscription policy, wary of alienating the very rural support base that sustained their revolutionary movement.

Tasked with reasserting control from an increasingly impatient leadership, French military tactics grew more brutal. The expeditionary forces – made up of seasoned troops from Algeria, Morocco, Tunisia, and the French Foreign Legion – found themselves fighting an enemy that refused to play their game. Under the command of General Vo Nguyen Giap, the Viet Minh had already adopted guerrilla warfare, avoiding direct engagements. Unable to square off with an ‘invisible adversary’, the infuriated French took their frustration out on the civilian populations they came across, burning whole villages, and indiscriminately killing men and women. The use of torture became widespread. Rape, too.

Today, the world is quite familiar with the US massacre at My Lai and other American war crimes – partly because of the films Americans made, and books they wrote, about themselves and what they did. But in 1948, French soldiers burned 326 houses and murdered more than half of the residents in My Trach village. Among the dead were 140 men, 170 women (many of whom were raped), 157 children, including 21 infants under 1 year old. However, unlike My Lai, outside of Vietnam the massacre of My Trach is largely unknown. Oh and the French military also dropped napalm (purchased from the US) on Viet Minh strongholds.

Interlude

“On all four sides was the ancient, untouched forest, empty of bird calls or the cold cries of the gibbons. Everywhere… nothing but weeds, dust, and thorns.” – Trần Tử Bình, The Red Earth

FROM A DISTANCE, a rubber plantation might appear like a forest for it is tall, green, and woodsy. But step inside and the illusion instantly dissolves. The air is too still. And it is oddly silent. For there are no birds. No squirrels, no deer. No butterflies or bees. No dragonflies humming above puddles. No flowers twisting up trunks, no ferns softening the earth.

For it is not a natural forest. It is a plot of land with an industrial purpose. A field of extraction designed to bleed latex, not to harbour or encourage biodiversity. For the Vietnamese who toiled on the plantations in colonial times, it was a realm of fever, and exhaustion. Instead of birdsong, they heard the tapping of knives, and the hiss of disease in their own lungs.

From this lifeless monoculture, the industrialised world turned. Rubber for Michelin tyres, waterproof capes, underwear and negligees, latex condoms, and countless other things like soles for the boots of soldiers trampling their way across foreign lands.

But before the plantations came to a place like Tây Ninh, the land would have been a mosaic of life. In the shadow of towering dipterocarps and Hopea trees, wild ginger would have bloomed and bamboos rustled in the wind. There would have been climbing yams and elephant ear taro. Orchids clinging to tree trunks.

A human visitor might have startled a civet cat or a sun bear. Or glimpsed a pangolin rolling into its shell. They might have heard macaques shrieking or gibbons hooting at dawn.

In the branches, barbets, drongos, and bulbuls would have randomly transmitted their own melodies. And at night, tree frogs would have belched out a chorus, cicadas would have chirred, and geckos clicked their tongues.

And beyond the forest, there would have been a land of plenty with rich soil and bountiful rice paddies. Around every wooden house, there would have been cassava, jackfruit, mango, longan, soursop – seemingly a fruit in every shade, and of every taste.

To combat fevers, leaves would be gathered, or bark would be scraped and placed in a brew. But then came the axe and then came the grid. And the trees that replaced the forest? They had shallow roots and no memory of what came before. How could they be trusted?

V

YOU WAKE UP, YOU GET DRESSED. You stroll to your office on Rue Catinat. You check the orders, prepare some telegrams. You let the routine convince you that all is well. ‘Another delay?’ your colleague grumbles, ‘What is it this time?’ A protest at the docks. An attack on the railway. A rumour that a French official in Hanoi has been killed on the road. It’s getting harder and harder to believe “order will be restored,” but you know not a single stakeholder would ever liquidate their business and call it quits. You’re stuck here till the bitter end.

“Did you know that even the Communists of France say they want to keep the colonies?” you tell your colleague. “Ha! Well how else would they pay for anything?” he snorts.

But what can you do? You keep writing letters trying to convey the uncertainty of the situation. As if they care – you picture them sitting on a terrasse after some gluttonous dégustation, sipping café or, more likely, brandy, admiring the Parisian ladies who stroll by, completely unaware that their latest fashions and accessories have all been made with vulcanised rubber.

Tipped over into madness, you grab a pen and scribble this nonsense:

Madames et Mademoiselles of Paris! That cinched waist, that imported taffeta swish – the coolies have toiled to make you très élégantes et chic. Did you not know?

The gum and bands that hold your whole ensemble together — Yes, pressed in the tropics by hands blistered from the heat. Oh, you didn’t know!

And that perfume you dab behind the ears? It once clung to the petals of flowers crushed in the fields of Tonkin. Well, I just thought you’d like to know...

As for the rubber soles beneath your dainty feet, well they trace their roots to trees tapped by men in chains, somewhere deep in the Congo… Oh, you didn’t know!

Well, never mind. Continue to shop then sip your demi-sec – even your love life bears the scent of latex.

Mesdames, please – let the colonies dress you, even as they burn. And stick to what you know. When one of the fat cats does reply, he insists all is well and that the governor has ‘personally assured the company’ that France will quickly reassert its control. But every hardliner that de Gaulle sends to clean up the mess only makes it worse. Across the city, you keep hearing of attacks, each more brazen than the last – just days ago, you heard that bloviating fool from Michelin, what’s his name, Piers Lemoine, insisting that trouble was only brewing in the countryside. ‘Mes amis’, he assured his little clique at the Cercle Sportif, ‘we have nothing to worry about in Saigon.’

And then? Yesterday a grenade was hurled into a milk bar on Rue Laval or was it d’Espagne? Three people were wounded, one seriously. No one claimed responsibility, but everyone knows what is happening. The Viet Minh had warned of escalation, and so, here you are…

This morning, you passed Café de la Paix, all covered in a harsh skeleton of wire mesh. You pressed on, ignoring the coos of the pousse-pousse riders – who knows who they are anyway?Inside the office, at times everything appears normal, but surely everyone knows the glory days are ancient history. No longer will you stroll alone in the evening, after dinner and drinks at La Croix du Sud. Too many eyes in the dark now. And even the well-do Annamites no longer greet you with a bright ‘bonjour’ or ‘bon soir, monsieur.’ No, no – goodbye to all of that.

And at night, the city rests uneasily. The only sounds you hear are the distant crickets or the buzz of a streetlamp – everyone laughed when it was suggested there would be a curfew. Now you’re at home, lying under your mosquito net and fantasising about things getting worse so you can justify packing up and leaving.

VI

WHEN WORLD WAR II ENDED, and the Japanese military presence in Indochina began to melt away, Madeleine O’Connell returned to Tây Ninh to find her plantation gutted, the land stripped bare. She might also have sensed a shift in the mood of the local population. The Việt Minh – the architects of Vietnam’s march to independence – were busily recruiting in the southern lands, and aggrieved plantation workers were a primary target for their anti-colonial movement [of note: they had initially destroyed plantations by burning or chopping down trees, but by the late 1940s, they were apparently more focused on thwarting the profits – the logic being that one day, the plantations would be theirs, and they would need the revenue7].

But, according to her obituarist, when rumours began to circulate that ‘Bà Lớn’ had survived, her former workers began to return – one by one, then in waves. By 1946, thousands (or so we are told) had come “home.” Rolling up her sleeves, Madeleine distributed quinine to fight malaria and other maladies, fed the hungry and even paid off debts that were not her own. Meanwhile, the legend of Madame Canon had spread far from Saigon – for her wartime courage, General Leclerc lauded her in his army dispatches.

But the war had not ended in Indochina. It was only just beginning, and the colonial plantations were increasingly a target for the Việt Minh, who wanted to hurt the colonial economy that the French were so desperately trying to rebuild. However, the O’Connell plantation was also a strategic target for military reasons. She was, the Việt Minh are said to have believed, ‘more dangerous than a general’. But when her Vietnamese manager was kidnapped in an attempt to intimidate her, she simply responded in kind, capturing Việt Minh operatives to negotiate her manager’s return – however, perhaps that was the final straw. On December 26, 1947, the order was given. Madame Canon was to be taken out.

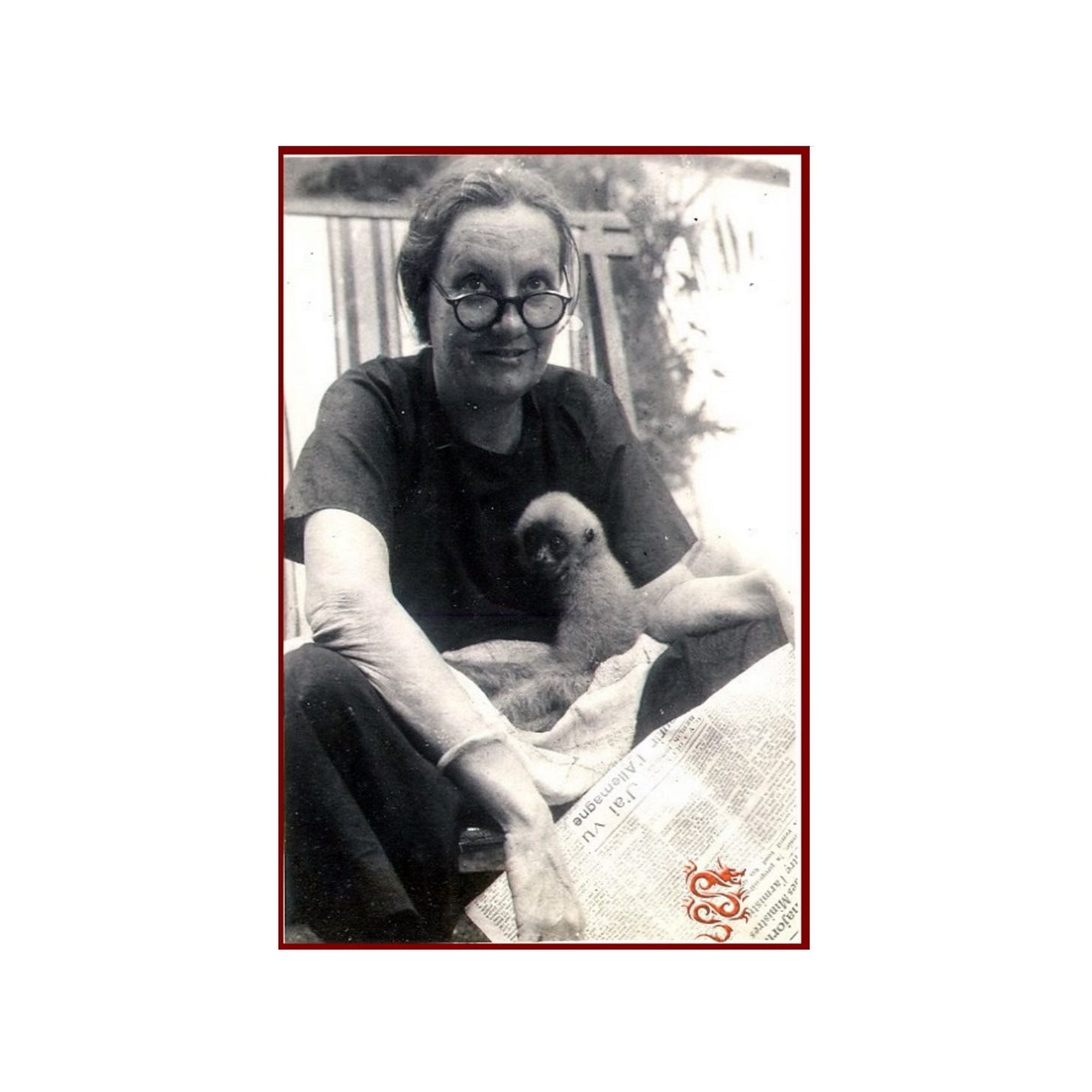

Four days later, Madeleine left her home in Tây Ninh for a routine inspection of her lands. She was accompanied by her son Roger, a local official, and – as always – Zazou the gibbon. A few kilometres down the road, her vehicle was ambushed and a firefight ensued. Madeleine was shot in the neck at close range and, after her attackers retreated, she was rushed to an airstrip and airlifted to Saigon, where she died at Grall Hospital. That night – from Saigon to Hanoi and beyond – the toasts must surely have rung out: “À Madame Canon – que son courage ne soit jamais oublié!”

VII

YOU HAD NEVER SPOKEN IN PERSON WITH MADAME O’CONNELL – you’d only seen her puttering down Rue Bonard in her dusty Peugeot 202, looking as if she were ready to lock horns with the tax collector. But in the month of March, 1947, everywhere you went, you heard the stories, and the legend grew with every telling.

The army depended on her, you were told – or overheard. She had an arsenal of artillery and ammunition at her plantation that she drip-fed to the soldiers. How did she do it? They say she dressed like a huntress and covered crates of rifles and grenades with straw, sacks of rice, and then doused it all with fish sauce to scare off the dogs – and the Japanese soldiers!

In one tall tale, when some Japanese soldiers tried to speak to her in clipped French, she climbed out of her car with her gibbon, Zazou, still on her shoulder, and threw some dead game at their feet – a hare, or a deer, or was it a boar? Well, never let the truth get in the way of a true story. "Vous avez faim, les garçons?" she said oh-so sweetly. Some say she even pocketed a few piastres in exchange before riding on to Saigon with a pistol tucked in her waistband.

You had no idea how she did it – or where she dumped the guns. But they say she transported seventeen tonnes of weapons in a week – seventeen tonnes?! How was it possible?

You weren’t there, of course. You were in the back of an office in Saigon, stamping permits, misfiling ledgers, trying not to look up when someone in uniform entered the room. And then, one day in March 1945, you heard that suspicions had grown among the Japanese. They sent some thugs – you’re not even sure who, but someone betting on the Japanese – to storm her plantation. One followed her into the kitchen. A scream was heard, and outside, the others laughed.

But when they entered, Madame Canon was standing there, blood on her apron, a mallet in her hand, and the feckless assassin dead at her feet. Perhaps one of her sons was there to witness it all? Yes, that’s how the story must have been shared at first.

Whoever told it said the thugs dragged her outside and frogmarched her through a village, where the peasants she once fed hurled abuse at her – pretty fickle, you’d have to say, but who knows what they have been told the French have done elsewhere. She was then tied to a bridge as if being prepared for an execution – her attackers demanding to know where she had hidden all of her artillery, and who her clandestine contact in Saigon was. But Madame Canon said nothing. They fired shots over her head to scare her, but still her lips were sealed. Oh, bravo, Madame! Bravo!

But she was not out of the woods yet. When the Japanese arrived, they dragged her away to be interrogated. Or rather, tortured – but still nothing. Or rather, she did say something. She corrected their god awful French mid-beating. Furious, they dragged her into a yard, dug a hole, and buried her up to her neck. Then, after placing a sword across her mouth – an execution reserved for warriors – they left her, assuming she would die.

But she didn’t.

When she woke, much to her surprise, Madame Canon had been removed from the pit, cleaned, and even bandaged. She was lying in a comfy bed in a clinic of some kind, and when she looked around, who did she see but several Japanese doctors and army officers – all of them bowing to her. Bowing!

Oh, is it too incredible to be true? Well, who knows? But you smiled all the way back to the office after hearing those thrilling stories, almost believing that you, too, could be so brave.

Epilogue

AFTER MADELEINE’S DEATH IN LATE 1947, her husband Daniel, their three sons and grandchildren remained where they had always been – Indochina – but the violent unraveling of their homeland continued. Madeleine’s nephew Maurice O’Connell was killed by Viet Minh soldiers in 1948, and two of her three sons, Patrick (a member of Commando Conus, a French special operations unit) and Guy (also in the French army, I assume), were killed on 14 January 1953, when their vehicle struck a mine on the trail of Tho-Not, near the Laotian border – likely during a patrol or supply run.

Following the historic Vietnamese victory at Dien Bien Phu in 1954, which marked the collapse of French military control in northern Indochina, the O’Connell plantation in Tây Ninh was either abandoned or destroyed. That same year, Daniel O’Connell’s house in Saigon was struck during a Viet Minh night raid, in which Luc Ottavi, a visiting family friend, was killed.

And yet, despite all of this personal tragedy and the escalating violence, Daniel remained. In fact, even after the last American helicopters disappeared into the sky on April 30, 1975 – when Saigon fell and Vietnam was reunified – Daniel O’Connell, by then 77 years old, and his youngest son Roger were still holding on in.

But one day in 1978, while they were at home in their apartment at 204 Võ Thị Sáu Street (just down the road from the old cemetery where Madeleine, Patrick, and Guy were buried), armed robbers – reportedly former soldiers from the South Vietnamese army – forced their way through the front door. They threatened to mutilate the fingers of the two Frenchmen before making off with every valuable item the O’Connells of old Indochina still possessed.

It was only then, remarkably, that Daniel turned to Roger – or perhaps it was the other way around – and said: We have to go back to France, a country that would surely prove strange and unfamiliar to them both. Daniel certainly did not bear exile well. He died in 1979. I am not sure what he did back in France but Roger passed away in 2000, not before the monks of Thanh-Diên Pagoda in Tây Ninh returned the ancestral tablets honoring Madeleine O’Connell to her grandson, and Patrick’s son, Gérard O’Connell, who along with his brother Alain was also born on Vietnamese soil.8

It was, I assume, a quiet act of remembrance. A low-key, cross-cultural exchange. As far as I know, no newspaper covered it. Certainly, no officials made speeches. But in a country that had long since closed the book on its colonisers, we can say that someone still remembered Bà Lớn – the barefoot Frenchwoman with her gibbon Zazou perched on her shoulder, a pistol in her pocket, a grin on her face, a glint in the eye…

I’d like to say, how could anyone forget her? But time marches on and today, the former O’Connell plantation lies buried beneath a fairly urbanised sprawl in Tây Ninh. Its once-forested grid overlaid by industrial sites and concrete on the outskirts of a fairly typical 21st century Vietnamese town. There’s a school, a handful of shops, some hair salons, a bunch of restaurants and kerbside cafés. It would be hard to argue that the spirit of Madame Canon could be found – or even sensed – anywhere. Even the old cemetery where she was buried in Saigon is long gone – in 1983, all the old graves were removed and their remains were exhumed to make way for a park that is, I am happy to say, full of life.

But even when the past is seemingly erased, it doesn’t have to disappear. Dig a little anywhere in Vietnam and you’ll likely unearth a story, one with tangled roots that have held firm beneath the surface. These tales are like trees, I suppose. Given time, and space, and just enough air, they grow back.

The story of Madame Canon is certainly far-reaching, complex, and deeply entwined with many other lives and rich histories. For years, decades even, it has remained buried in fertile soil, just waiting for the right moment to rise up and be seen.

Like today.

Enjoy this story? You can make a small payment via Ko-Fi or directly via Paypal below.

Viet Minh is short for Việt Nam Độc Lập Đồng Minh Hội, which translates to League for the Independence of Vietnam. Following the Geneva Accords in 1954, which split Vietnam at the 17th parallel, the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (North Vietnam) became formalised.After this point, the name Viet Minh gradually faded from official use, as the government transitioned to using state structures, which involved introducing the North Vietnamese Army (NVA)/

The family also owned a plantation in Thu Dau Mot, which they later sold.

In southern Vietnam, there is a long-standing reverence for the powerful, protective female spirit known as Bà Đen (literally ‘the Black Lady’) of Bà Đen mountain. According to legend, Bà Đen was a young woman who died resisting an assault. She was later deified as a guardian of the land and the people. In this cultural landscape, a woman like Madeleine – independent, and as will soon see, fearless, and self-sacrificing – would have struck a deep and familiar chord.

Writing of the mood in Saigon at this time, Christopher Goscha: “Vietnamese rickshaw drivers in Saigon would have understood that the Japanese soldiers strolling down Rue Catinat had upended the colonial order and the racist assumptions on which it rested.”

This point is what historians, such as Goscha, say marks the beginning of a 30-year war for Vietnamese Independence.

Meanwhile, in the north – on November 23, 1946, French naval vessels and field artillery bombarded the Vietnamese and Chinese quarters of Haiphong – the port city in the northeast of Vietnam (Tonkin at the time). Casualty estimates vary from 3,000 to 20,000, but the most widely accepted figure is that around 6,000 civilians were killed.

Today Vietnam is a major global player in natural rubber, contributing nearly 9 % of the world’s output, and boasting some of the highest yields per hectare in Asia.

I am not sure when Patrick and Alain left Saigon, but it seems plausible they might have left in the 60s when they would have been of university going age.

Great story, well told sir!

Good one! Thanks