Veto's Bar in Danang

A non-fiction story about a US soldier from Hawaii, who deserted the army to marry a local girl in Danang.

ONE DAY, SOMEDAY SOON, if I’m lucky, I’d like to find a bar in Danang called Veto’s.

It’d be a pretty unassuming place from the outside – no neon signs or glitz; no throbbing beats – and the interior would be old-fashioned and snug. I’m thinking, mellow lighting, non-intrusive tunes and a solid, wooden bar for propping up punters. You could get away with reading a book at Veto’s, but if you want to come clean and admit the book is a pretence, you’d easily get talking to someone, too.

A solo traveller who happened upon Veto’s and stepped in the door would immediately appreciate this ‘ấm cúng’1 ambience. He or she’d order a bottle of the local brew, or a glass of wine, and ask if there’s a food menu. The bar staff would slide over a menu with a mix of Danang staples and, surprising the traveller, a few Hawaiian dishes – say, baked manapua, or a poke bowl with local yellowfin tuna, maybe some lomi-lomi salmon…

Before ordering a dish or two, the traveller would look up over the menu and start to notice the black&white street photography and portraits of Danang locals from the 1970s as well as some vintage images of Hawaii that’d further pique a curious mind.

As their beverage arrives (hopefully with no umbrellas), the traveller would lean in and ask: “Em/ anh oi, tell me – what’s the connection with Hawaii?”

“Because, Veto Baker,” they’d be told.

Um, who?

You see Veto Huapili Baker was a US marine from Hawaii, who was stationed near Danang during the American-Vietnam war. He fell for a Vietnamese woman called Mai, and he wanted to get married, but the US military police said: “No dice, Private. Back to your barracks and stay put.”

So, because, all isn’t fair in love and war, in October 1972 , Veto slipped away in the dead of night (or maybe in the middle of the day, which ever you prefer to visualise) and married her anyway.

Officially he’d deserted, but Veto didn’t ‘join the other side’. He wasn’t a traitor. He just wanted to be with his lady. As she was from Danang, a city he knew well enough, and as relocating would have been too much of a risk, Veto stayed with her family, hoping neither the Vietnamese nor American military would come looking for him.

With his Hawaiian complexion and slender build, Veto didn’t stand out too much. So, to earn his keep (or, escape the in-laws?), he got out of the house plenty. Some have said he fixed motorcycles. Some believe he was part of a road construction crew up in the mountains beyond Danang. One source I found claims he spent his time hunting and teaching English.

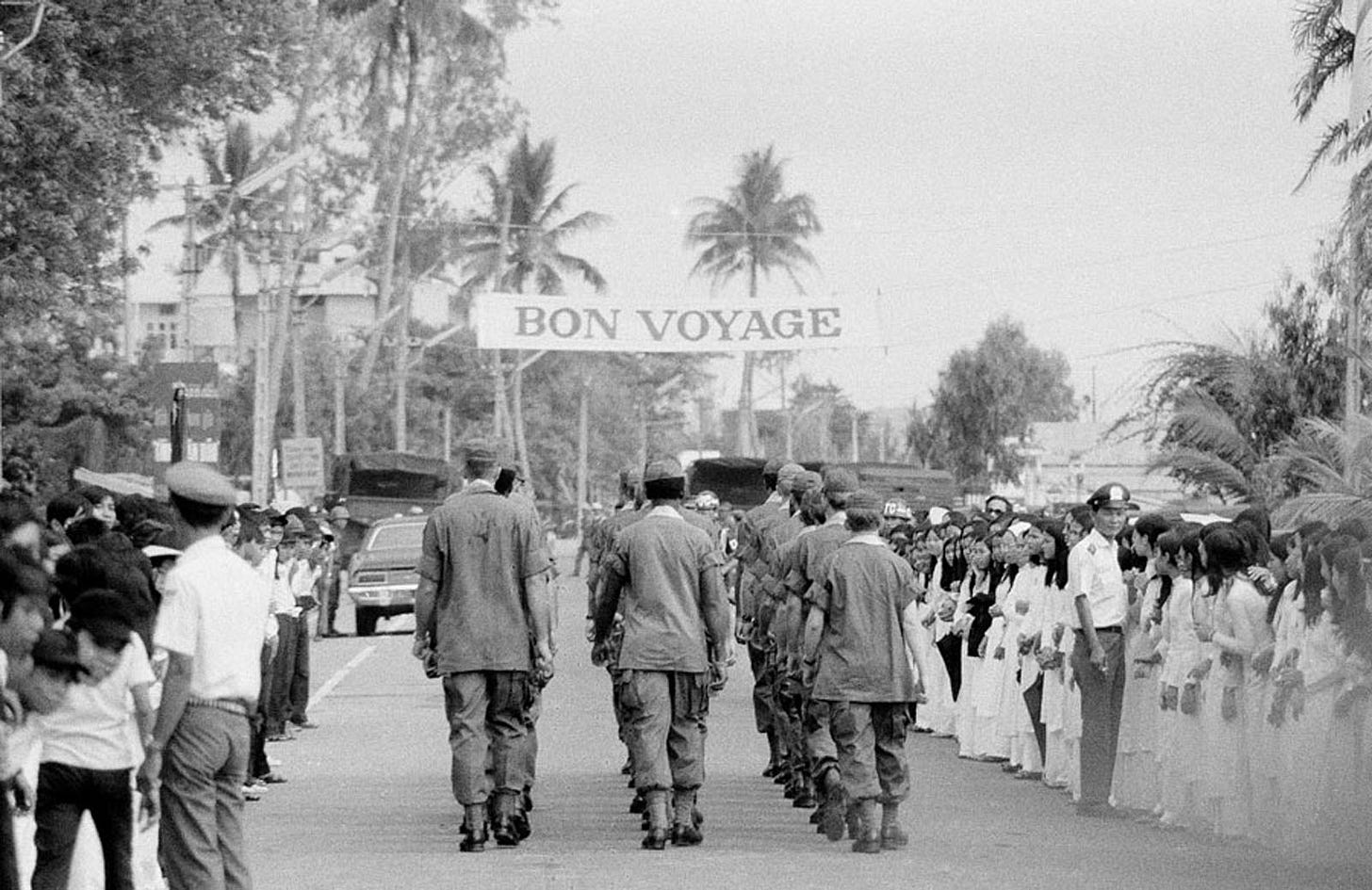

Obviously while residing and working in Danang, after the US had pulled out, Veto became known to the Vietnamese authorities, and they were undoubtedly keen for this known-unknown to leave. Sure, Veto might have deserted the enemy’s army for love but they wouldn’t have bought that one in a hurry. Any American ‘stay behind’ just couldn’t be trusted. Veto and his wife were visited at home and taken away a couple of times, and released a couple of times, but eventually a decision must have been made to send him on his way.

So, in 1976, Veto was taken to Saigon, turned over to the Red Cross, and sent to Thailand, before eventually winding his way home to Hawaii with a pregnant Mai and two children.

I was told that the DIA office had some contact with him in the late 1980s, wanting to know more about his AWOL experiences from 1973–75. What he told them I can’t tell you, but there were tales of POW in the area2. No doubt they were more interested in that rather than what Veto had for breakfast, lunch and dinner (I, for the record, am quite interested in what Veto had for breakfast, lunch and dinner).

One source told me that he’d last heard from Veto many, many years ago and he wasn’t sure of Veto’s whereabouts, or even if he was alive. Resilient researcher that I am, I turned to the greatest detective of them all (yeah, Facebook) and dug up a name that looked a lot like Veto’s. That’s to say, a series of very Hawaiian forenames and the surname Baker.

It turned out to be Veto’s brother, who is a kumu hula (master hula teacher) and a performer in Hawaii. I dropped him a line and he replied to tell me that Veto was alive and well, far from Hawaii in a southern US state, to be closer to some of his kids (he’d had five in total) and many grandkids. He added that Veto and Mai’s story made him love the Broadway show Miss Saigon but in the play, the marine leaves the girl. But his brother? “Veto loved Mai so much that he went AWOL,” he wrote.

I thought about pushing for more, maybe trying to get a direct email or a number. Maybe I’d find out what Veto really did in Danang, and what he ate for breakfast, lunch and dinner, and what the hell his missus’ family originally made of this strange alliance in the first place, and, years later, how he reflected on that time when he was head over heels and AWOL.

But… then I thought, well, maybe what little I know is enough, enough at least to dream up the existence of Veto’s Bar in Danang, a humble tribute to a forgotten story.

Because I could tell that his brother views Veto’s actions as heroic. And I do, too. An ordinary Joe doing an extraordinary thing. Sticking two fingers up to Uncle Sam’s heinous military machine, and, through his actions, if not his words, turning to Mai, asking her the only question that counts for lovers on the run: ‘Take my hand quick and tell me, what have you in your heart.’ 3

And today, many, many moons later, surrounded by their kids and grandkids, I guess we can say Veto and Mai’s hearts were filled with answers…

So, look – here’s the deal. If anyone of you is moved by this story, and actually wants to open a bar in Danang, and name it after Veto, you have my blessing – just one thing: promise me you don’t turn it into a tiki bar, serve enormous blue cocktails with garish umbrellas, or make the staff wear Hawaiian shirts, and offer garlands of flowers while cooing aloha when punters walk in the door.

Because, Veto didn’t want to draw attention to himself, and I guess he still doesn’t — so, neither should the bar.

Cosy in Vietnamese

For more on tall tales of POW, please see ‘Salt & Pepper’, published online by Mekong Review and free to read.

From A. E. Housman’s ‘A Shropshire Lad: XXXII. From far, from eve and morning.’